THE CAVE FONT DE GAUME

Photo by Don Hitchcock 2008

I’m a student, a researcher. Therefore, my enthusiasm for my next trip begins months before the actual starting date. How do I prepare? I scour travel sites, blogs, reviews, books on history and art, any resource that tells the story of the places I want to visit. Even more important, friends share their tips. Did I mention that I hope you will share yours too in this newsletter?

In Europe, invasions define much of what the guide books suggest. In the area we identify as modern-day France, the Greeks, Romans, Visigoths, Normans, and Franks changed the landscapes of the original Gaulic tribes.

But even before such identifiable groups were chronicled, the earliest Paleolithic humans, commonly called Cro-Magnum, settled in the area. It was this group of early humans whose cave paintings in the Dordogne Valley of southwestern France challenged any “caveman stereotypes” I had previously entertained.

Okay, I admit it. My initial knowledge of prehistoric humans came from panoramas of families dressed in animal skins in the Carnegie Natural History Museum in Pitttsburgh and the tv show The Flintstones. But two reindeers in the farthest reaches of a cave called Font de Gaume changed all that. Let me explain.

The Dordogne Valley was settled as early as 25000 BCE , but traces of the people who lived there were largely forgotten until the 20thcentury when a local teacher or some crazy kids literally stumbled into the side of a mountain. There they discovered caverns that had been inhabited by prehistoric peoples for millenniums. In these caves, a mesmerizing world of paintings was created by artists around 17000 BCE.

Of course, the most famous cave in the Dordogne is Lascaux with its many caverns of nearly 900 cave drawings of horses, bison, ibex, and a host of other species, including one human. Unfortunately the cave was closed to visitors in 1963 over concerns of deterioration.

But, as is often the case, three Disney-like models (called Lascaux II-IV) were designed for the tourist trade. These replicas faithfully copy the original caves down to the dimension of the caverns. The composition of the paint, and how the artists created their visions is also carefully replicated. Any one of these versions is worth a visit. Each are stunning.

Just like the rest of the tourists, my husband, George, and I, along with our intrepid friends Bill and Linda, craned our necks and gaped at the ceilings and walls with herds of animals bearing down on us. Still, something was lost in translation.

We needed to see cave drawings in their original setting. So we set off to find Font de Gaume, a smaller cave still open to the public. These days you can only get tickets online, so do your research early. In fact, if you are interested in going, I would make a trip sooner rather than later, as there is no promise the cave will be open for much longer.

We started our tour in the outer mouth of the cave where the community had lived. Then we squeezed ourselves into a narrow, twisting tunnel called the Rubicon, the term Julius Caesar coined for passing the point of no return.

Ignoring the warning, we sucked in our breath, crouched down, and reached a more welcoming gallery with more cave paintings. At least, George’s 6’4” frame found it much more manageable, but the tight corridor was still a challenge.

How did the prehistoric painters manage the perspective and clarity of their paintings when they must have been standing practically on top of them?

Speaking in an animated French, our guide trained his lazer on the outlines of numerous bison, a galloping horse, the head of an antelope, and other mammals, many of them startling in their red ochre bodies and black outline. Others faded into cave walls deteriorating under the seepage of time. But each told its own story with an artistic sophistication that negated any stereotypes we had previously held. .

CRO-MAGNUM ARTISTS IN THE CAVE FONT DE GAUME

By Charles R. Knight, 1920. Permission: Public Domain

In the gaps of our guide’s narrative, I could clearly see the artists of these polychromatic paintings finding their way into the recesses of the mountain. Why would they choose such an inaccessible space? As the air became thinner and the light dimmer, I could only imagine a ritual taking place, possibly as the result of a hallucinogenic experience.

By torchlight perhaps a shaman painted the bison whose chest curved out in concert with the natural relief of the stone. Was this painting to ensure a successful hunt? Maybe the pubic triangle of the female related to a fertility rite. Animals of species not native to the area might have been powerful totems who could guide these communities into alternate universes.

We were brought back to the real world when we saw the painting of two reindeer with their contours barely visible but their beauty indescribable.

THE TWO REINDEER, A VISUAL REPRESENTATION

Henri Breuil; Louis Capitan, 1902. Public domain

In this cave painting, 9 feet wide, the larger stag with his sweeping antlers leans down to lick the forehead of a smaller female lying on her side, probably in the process of giving birth. in the original cave painting her face shows an exhaustion that only her mate could comfort.

Eighteen thousand years ago, an artist recorded this startling tenderness which connected me more deeply to our paleolithic ancestors than any other experience I have ever had. Many nights when my “monkey mind” won’t settle, this image quiets my thoughts. It is a Wonder.

I would never argue with the theories of natural selection and environmental adaptation as the basis of the biodiversity in this universe. I’m not an evolutionary biologist nor do I have friends named Darwin. I am always in awe of a column of ants two miles long that carries food back to their nest. My night sky fills with the cosmic dance that is the universe. The bike paths I ride enjoy the rhythm of asters and goldenrod in seasonal waves. Still. . .

Biology alone can’t account for human survival. The gentle tenderness of some paleolithic art might very well be the ultimate scaffolding we need to survive, the true wonder of the world that still sustains us today.

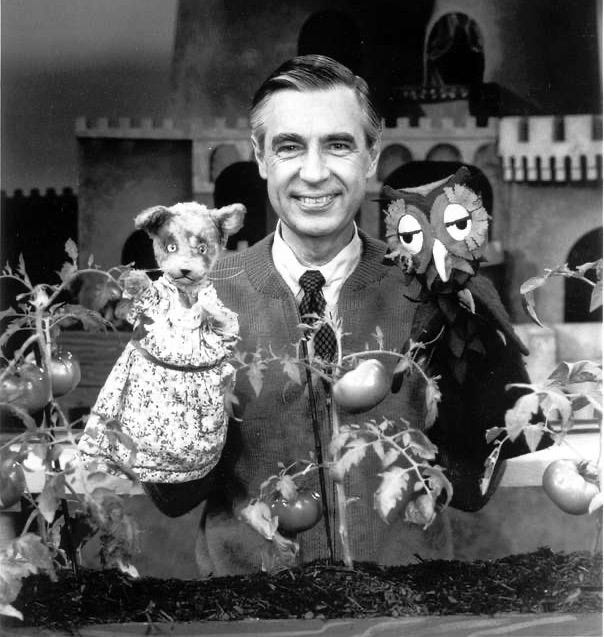

It can be tiring always to be striving, adapting, competing, and never satisfied with our lives. If we think about it, when we are exhausted, only the kindness of others helps us to shoulder the anxiety of contemporary living. Just ask two reindeer in a cave 17,000 years old. You might also ask the man who comforted us as children, Mr. Rogers.

There are three ways to ultimate success:

The first way is to be kind.

The second way is to be kind.

The third way is to be kind.

Love the way you focused on the touching moment when you saw the deer painting. The other pictographs were about hunting or seducing game. But that deer painting seems so human that it crosses the centuries.

i am busy working on a last event at our old farm and a journey to the new farm, though that happened awhile ago.